Key Takeaways:

- Non-oxidized LDL with high HDL, low triglycerides and low levels of inflammation shouldn’t be a cause for concern.

- However, oxidized LDL, especially with high inflammation, high triglycerides and low HDL is a ticking-time bomb for heart disease.

- A healthy ketogenic diet can reduce your risk for heart disease.

By now, most people are familiar with the decades-old lipid hypothesis, postulating that reducing levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol can save lives and prevent cardiovascular disease. However, over decades of clinical trials and studies have shown inconsistent and contradictory results to this theory. Lowering LDL for heart attack prevention does not work for everyone! [1] [2]

Despite its reputation as the “bad cholesterol”, LDL serves as an aid to many important physiological processes in the body. It’s rarely given credit for its role in delivery of cholesterol to cells to serve in the structure of cell membranes, synthesis of steroid hormones, and more.

Doctors often prescribe statin drugs (Lipitor, Lescol, Livalo, Altoprev, Crestor, Ezallor, Pravachol, Zocor, and FloLipid) to reduce the liver’s production of cholesterol by blocking an enzyme called HMG-CoA reductase. They are thought to reduce cardiovascular mortality and morbidity by lowering LDL. [3] However, while we can be confident they do lower cholesterol, they have failed to substantially improve cardiovascular outcomes. Statin advocates use a statistical tool called relative risk reduction (RRR) to amplify the trivial benefits and minimizing adverse effects. [4] These adverse effects include significantly higher odds of myopathy (muscle pain or weakness) and diabetes. [5] Furthermore, the benefits seen from statins may actually be from pleiotropic effects, mediated by a reduction in systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and platelet hyper-reactivity. [6] [7] [8] [9] Ezetimibe is another cholesterol medication on the market to lower LDL and increase HDL by preventing the absorption of bile acid in the small intestine.

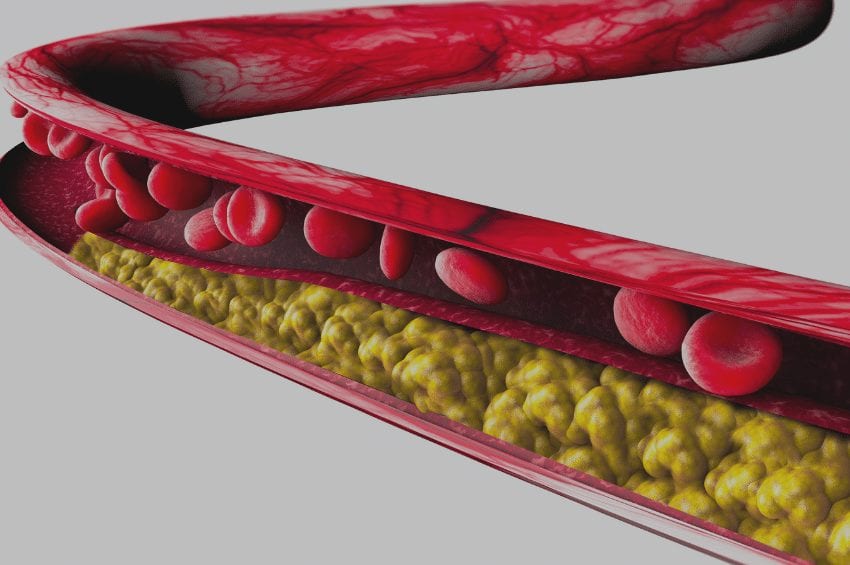

Cutaway of an LDL particle.

Currently, the recommended LDL target goal of <70mg/dl does not entirely eliminate cardiovascular risk. With advancements in medications, specifically now with PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies, it’s possible to bring LDL as low as 15mg/dl. There are studies showing reduction in atherosclerotic plaque, but there have also been reported increases in strokes, dementia, depression, hematuria (blood in the urine), and cancer along with these extremely low LDL levels. The long-term effects and safety of low LDL are still being explored. [10]

Because of the lipid hypothesis, people have believed LDL levels are the gold standard to predict future risk of heart disease. Thanks to the ketogenic/low-carb movement, inflammation is starting to be understood as a root cause of not only heart disease but many other chronic conditions. We can confidently say that saturated fat does not clog the arteries, and chronic inflammation is the culprit behind coronary heart disease. [11]

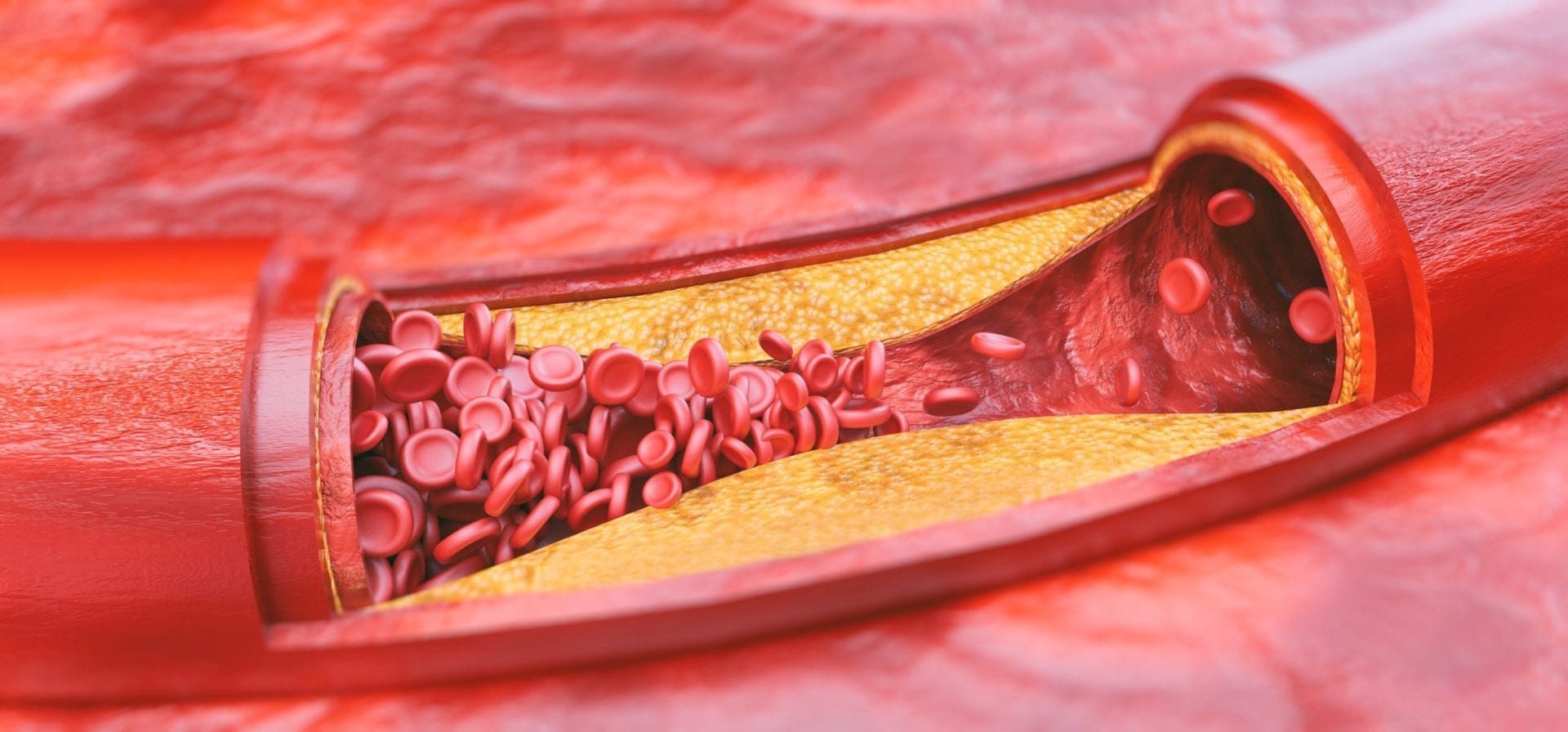

When the lining of arterial walls is damaged from inflammatory high blood pressure, smoking, sugar consumption, infections, environmental pollutants, auto-immune disease, etc., LDL comes along to help repair the wreckage. Through invasion of the arterial cell walls, LDL triggers plaque formation to repair these cracks. Stable LDL plaques themselves are not the cause of cardiovascular disease. [12]

So, why are LDL and plaques thought to be a problem? When circulating LDL becomes inflamed and oxidized by free radicals, atherosclerosis (plaque build-up in arteries) progresses. Oxidized-LDL is the problem! This damaged LDL through oxidation is taken up by large white blood cells in our immune system called macrophages. Macrophages are then transformed to lipid-laden foam cells and lead to instability of the plaque, ultimately causing heart attacks. [13] Every time you consume food cooked with vegetable oil, these dangerous oxidized fats are entering your body. It’s no secret that vegetables oils are contributory to heart disease. [14]

So, why are LDL and plaques thought to be a problem? When circulating LDL becomes inflamed and oxidized by free radicals, atherosclerosis (plaque build-up in arteries) progresses. Oxidized-LDL is the problem! This damaged LDL through oxidation is taken up by large white blood cells in our immune system called macrophages. Macrophages are then transformed to lipid-laden foam cells and lead to instability of the plaque, ultimately causing heart attacks. [13] Every time you consume food cooked with vegetable oil, these dangerous oxidized fats are entering your body. It’s no secret that vegetables oils are contributory to heart disease. [14]

Studies have confirmed increased levels of circulating oxidized LDL increases risk of cardiovascular disease. [15] In fact, a study showed oxidized LDL levels predict progression of atherosclerosis independent of cholesterol content as well as number and size of LDL particles. High levels of inflammation with an LDL count <130 was a higher risk of cardiovascular disease than low levels of inflammation with LDL levels >160. [16] Inflammation and oxidized LDL are the real culprits behind heart disease!

What does this have to do with keto? Many studies demonstrate the reduction of carbohydrates to levels that induce a state of nutritional ketosis benefit cholesterol levels. [17] [18] [19] Ketosis is particularly beneficial in reducing triglycerides, but it also reduces total cholesterol while increasing HDL (the “good” cholesterol). [20] Low-carb diets have also been reported to increase the particle size and volume of LDL, which is thought to be less atherosclerotic than the small, lower-density LDL particles. [21]

LDL particles binding a cell membrane surface.

In addition to dietary sources, cholesterol can also be synthesized endogenously (inside the body), and a key enzyme in this pathway (HMG-CoA, the same enzyme inhibited by statins) is activated by insulin. We know high levels of glucose from a high-carb diet stimulate insulin and thus stimulate enzymes to make endogenous cholesterol. A low-carb diet will have the opposite effect, which is likely be another mechanism of the ketogenic diet that improves cholesterol profile. Despite unfounded opposition, studies strongly demonstrate the benefits of a ketogenic diet regarding these cardiovascular risk parameters. [22]

While a ketogenic diet may not be appropriate for everyone, such as those with variations of the APO-A2 gene, [23] many people will benefit from its anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Along with the elimination of vegetable oils and processed foods, a diet high in fat and low in carbohydrates will reduce inflammation and help lower your risk for heart disease. Before implementing any dietary or medication changes, discuss with your doctor if you’re an appropriate candidate.

References

Texon, M. E. Y. E. R. (1989). The cholesterol-heart disease hypothesis (critique)–time to change course?. Bulletin of the New York academy of medicine, 65(8), 836.

DuBroff, R. (2018). A Reappraisal of the Lipid Hypothesis. The American journal of medicine, 131(9), 993-997.

Simic, I., & Reiner, Z. (2015). Adverse effects of statins-myths and reality. Current pharmaceutical design, 21(9), 1220-1226.

Diamond, D. M., & Ravnskov, U. (2015). How statistical deception created the appearance that statins are safe and effective in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Expert review of clinical pharmacology, 8(2), 201-210.

Naci, H., Brugts, J., & Ades, T. (2013). Comparative tolerability and harms of individual statins: a study-level network meta-analysis of 246 955 participants from 135 randomized, controlled trials. A Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 6(4), 390-399.

Desai, C. S., Martin, S. S., & Blumenthal, R. S. (2014). Non-cardiovascular effects associated with statins. A Bmj, 349, g3743.

Blake, G. J., & Ridker, P. M. (2000). Are statins anti-inflammatory?.  Trials, 1(3), 161.

S Antonopoulos, A., Margaritis, M., Lee, R., Channon, K., & Antoniades, C. (2012). Statins as anti-inflammatory agents in atherogenesis: molecular mechanisms and lessons from the recent clinical trials. Current pharmaceutical design, 18(11), 1519-1530.

Diamantis, E., Kyriakos, G., Victoria Quiles-Sanchez, L., Farmaki, P., & Troupis, T. (2017). The anti-inflammatory effects of statins on coronary artery disease: an updated review of the literature. Current Cardiology Reviews, 13(3), 209-216.

Bandyopadhyay, D., Qureshi, A., Ghosh, S., Ashish, K., Heise, L. R., Hajra, A., & Ghosh, R. K. (2018). Safety and efficacy of extremely low LDL-cholesterol levels and its prospects in hyperlipidemia management. Journal of lipids, 2018.

Malhotra A, Redberg RF, Meier P. Saturated fat does not clog the arteries: coronary heart disease is a chronic inflammatory condition, the risk of which can be effectively reduced from health lifestyle interventions. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1111-1112.

Ravnskov, U., de Lorgeril, M., Diamond, D. M., Hama, R., Hamazaki, T., Hammarskjöld, B., … & McCully, K. S. (2018). LDL-C does not cause cardiovascular disease: a comprehensive review of the current literature. Expert review of clinical pharmacology, 11(10), 959-970.

Yu, X. H., Fu, Y. C., Zhang, D. W., Yin, K., & Tang, C. K. (2013). Foam cells in atherosclerosis. Clinica chimica acta, 424, 245-252.

DiNicolantonio, J. J., & O’Keefe, J. H. (2018). Omega-6 vegetable oils as a driver of coronary heart disease: the oxidized linoleic acid hypothesis. Open heart, 5(2), e000898.

Gao, S., Zhao, D., Wang, M., Zhao, F., Han, X., Qi, Y., & Liu, J. (2017). Association between circulating oxidized LDL and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 33(12), 1624-1632.

Gao, S., Zhao, D., Qi, Y., Wang, W., Wang, M., Sun, J., … & Liu, J. (2018). Circulating oxidized low-density lipoprotein levels independently predict 10-year progression of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis: a community-based cohort study. Journal of atherosclerosis and thrombosis, 43299.

Volek, J. S., Phinney, S. D., Forsythe, C. E., Quann, E. E., Wood, R. J., Puglisi, M. J., … & Feinman, R. D. (2009). Carbohydrate restriction has a more favorable impact on the metabolic syndrome than a low fat diet. Lipids, 44(4), 297-309.

Shai, I., Schwarzfuchs, D., Henkin, Y., Shahar, D. R., Witkow, S., Greenberg, I., … & Tangi-Rozental, O. (2008). Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(3), 229-241.

Brehm, B. J., Seeley, R. J., Daniels, S. R., & D’alessio, D. A. (2003). A randomized trial comparing a very low carbohydrate diet and a calorie-restricted low fat diet on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 88(4), 1617-1623.

Sharman, M. J., Kraemer, W. J., Love, D. M., Avery, N. G., GoÌmez, A. L., Scheett, T. P., & Volek, J. S. (2002). A ketogenic diet favorably affects serum biomarkers for cardiovascular disease in normal-weight men. The Journal of nutrition, 132(7), 1879-1885.

Volek, J. S., Sharman, M. J., & Forsythe, C. E. (2005). Modification of lipoproteins by very low-carbohydrate diets. The Journal of nutrition, 135(6), 1339-1342.

Paoli, A., Rubini, A., Volek, J. S., & Grimaldi, K. A. (2013). Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. European journal of clinical nutrition, 67(8), 789.

Corella, D., Peloso, G., Arnett, D. K., Demissie, S., Cupples, L. A., Tucker, K., … & Ordovas, J. M. (2009). APOA2, dietary fat, and body mass index: replication of a gene-diet interaction in 3 independent populations. Archives of internal medicine, 169(20), 1897-1906.