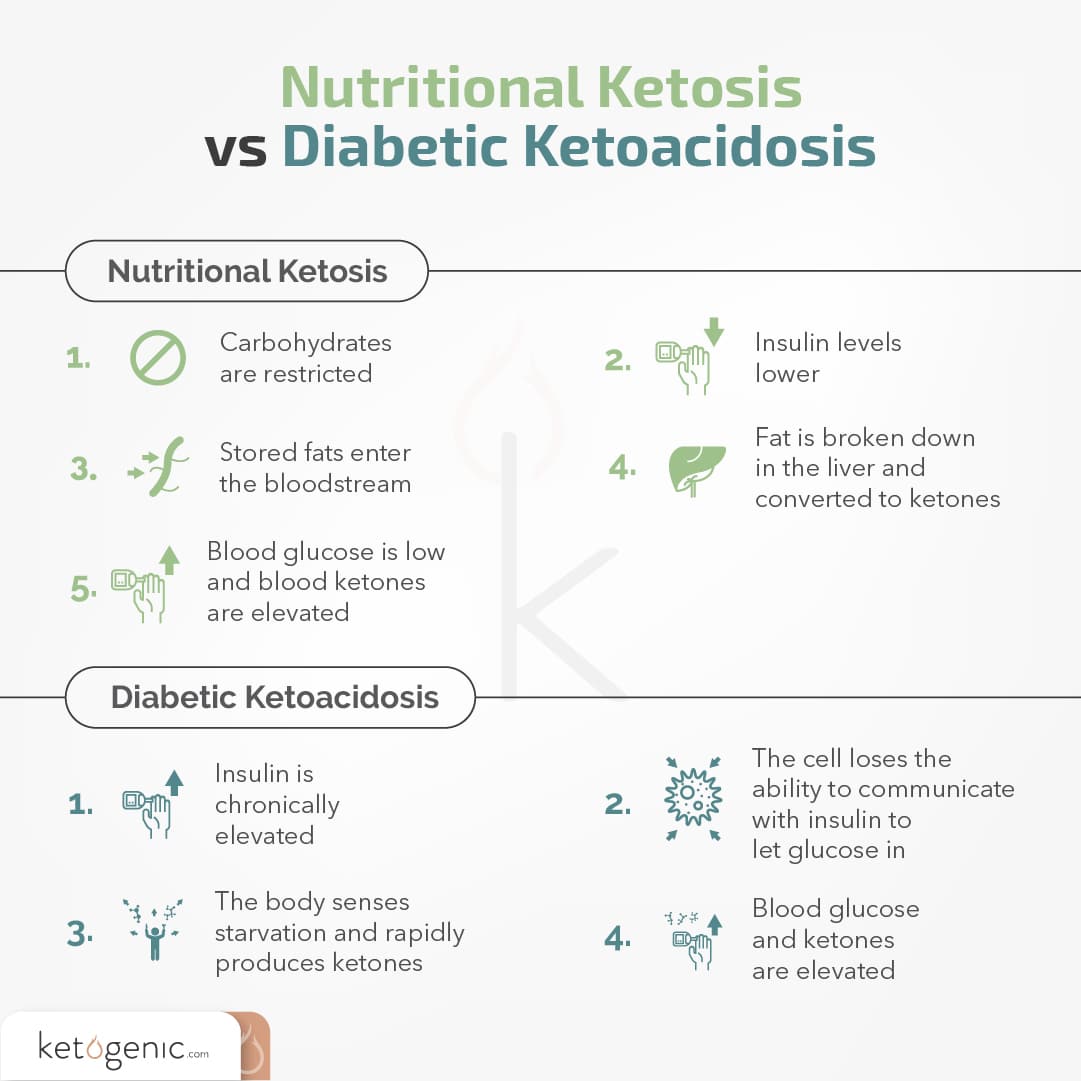

Ketosis and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) are two completely different things that shouldn’t be confused, despite the similarity in name. Ketosis can be especially beneficial for your health whereas ketoacidosis can be life-threatening. To clear up any confusion, let’s discuss what ketoacidosis (DKA) is and the difference between the two.

What is Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)?

Diabetic ketoacidosis refers to a complication of type 1 diabetes. DKA is a life-threatening condition caused by dangerously high levels of blood sugar and ketones. The blood becomes too acidic, which can alter the normal functioning of internal organs like your kidneys and liver. Ketoacidosis requires prompt treatment, and it can occur quickly, often developing in less than 24 hours.

Ketoacidosis usually happens in type 1 diabetics and those who don’t produce any insulin [1] [2]. DKA can also occur in those with type 2 diabetes with little or no insulin production.

What are the Symptoms of Ketoacidosis?

Symptoms of ketoacidosis include:

- Frequent urination

- Extreme thirst

- Dehydration

- Vomiting and nausea

- Stomach pain

- Exhaustion

- Extra fruity-smelling breath

- Shortness of breath

- Feelings of disorientation and confusion

DKA symptoms might also be the first indication of diabetes.

What Causes Ketoacidosis?

Diabetic ketoacidosis can be caused by several factors, including improper diet, illness, or not taking the proper dose of insulin.

A leading trigger for DKA is poor diabetes management. If a diabetic misses one or more insulin doses or doesn’t use the right amount of insulin, it can lead to DKA.

Certain illnesses, infections, and drugs can also prevent your body from properly utilizing insulin, which can lead to DKA. For example, urinary tract infections and pneumonia can trigger DKA.

Other possible triggers of DKA are:

- A heart attack

- Alcohol misuse

- Stress

- Malnutrition in those with a history of excessive alcohol consumption

- Misusing drugs, particularly cocaine

- Certain medications

- Severe dehydration

- Acute major illnesses, such as pancreatitis, myocardial infarction, or sepsis

The main risk factor for DKA is type 1 diabetes. One study of people with DKA showed that 47% had known type 1 diabetes, 27% had newly diagnosed diabetes, and 26% had known type 2 diabetes [3].

If you have diabetes, you have a higher risk of developing DKA if you don’t follow your routine for blood sugar management recommended by your doctor or medical practitioner. Diabetics who are losing weight often have low to moderate ketone levels, but this doesn’t increase the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis if blood sugar is properly managed and within normal ranges.

Other risk factors for DKA include:

Testing Ketones

A diagnosis of DKA can be overwhelming, but you can monitor and improve your health and blood sugar with the right methods and support system.

Blood Ketones

A simple blood test can be used to detect the level of ketones in your blood.

For reference, individuals not on a ketogenic diet have normal to low blood ketones around 0-0.5 mmol/L. Beginning ketosis is around 0.5 mmol/L, and moderate nutritional ketosis is between 0.5–1.5 mmol/L. Most experts believe blood ketone levels in the range of 1.5–3.0 mmol/L (without exogenous supplementation) indicates starvation ketosis or a higher risk for DKA. Blood ketone levels of 3 mmol/L and above may be a sign of DKA and warrants immediate medical attention.

Urine Ketones

You can also test your urine for ketones at home to make sure your ketones are in the safe range.

For reference, normal to low urine ketones should be below 0.5 mmol/L. If you’re beginning ketosis, your urine ketone levels should be above 0.5 mmol/L, and nutritional ketosis is in the range of 0.5-3 mmol/L. Most health experts consider levels above 5mmol/L to be a higher risk for ketoacidosis and urine levels above 10 mmol/LU to be DKA, where medical attention is necessary.

The risk of DKA increases as ketone levels rise, and blood sugar is above 250mg/dL (14 mmol/L).

Blood ketone tests are a great way for those with diabetes to monitor ketone levels. Blood ketone tests measure beta-hydroxybutyric acid – the main ketone involved with ketoacidosis.

If you or someone you love has diabetes and is showing the symptoms of DKA, call 911 or go to your doctor or emergency room immediately. Immediate treatment for DKA can be lifesaving.

How is DKA Diagnosed?

To diagnose DKA, a doctor typically performs a physical exam and a blood test to check your glucose, acidity, and electrolytes. Your blood test results help your doctor determine if you have DKA or other complications of diabetes. Your doctor might perform a chest X-ray, a urinalysis for ketones, an electrocardiogram, and other tests.

You can monitor your ketones and blood sugar with over-the-counter test kits. Some glucose meters can also check for blood ketones.

What is the Treatment for Ketoacidosis?

If you have DKA, treatment typically involves fluids by mouth or through a vein, intravenous insulin, replacement of electrolytes like potassium and sodium, and screening for other problems. DKA often improves with treatment within 48 hours.

The first step after recovering from DKA is to review your recommended insulin and diet management program with your doctor. It’s important you have a clear understanding about what you have to do to keep your diabetes and blood sugar under control.

You might want to keep a daily log to track your meals, snacks, medications, ketones, and blood sugar. If you’re sick with the flu, a cold, or an infection, stay alert for any possible symptoms of DKA.

What is Ketosis?

Ketosis indicates the presence of ketones, which isn’t harmful. For example, if you’re fasting or on a low-carbohydrate diet, you can be in ketosis where you have higher than usual levels of ketones in your urine or blood, but not high enough to cause acidosis. When your body burns stored fat, you produce chemicals called ketones.

A low-carb diet can trigger ketosis because you have less glucose in your blood, which causes your body to burn fat for energy instead of sugars.

People try ketogenic diets for various reasons, including to help with weight loss. It’s always best to talk to your healthcare practitioner before making any dietary changes.

Concluding Thoughts

Ketosis and ketoacidosis are two completely different things. Ketosis is a safe and completely natural state of metabolism, whereas diabetic ketoacidosis is a potentially life-threatening dangerous condition typically seen in people with poorly controlled diabetes.

If you have any concerns about your blood sugar or ketoacidosis, visit your doctor or healthcare practitioner.

Check out our other articles for more info on ketoacidosis:

References

Mayo Clinic. Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Diabetic ketoacidosis – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic

American Diabetes Association. Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Ketones. DKA (Ketoacidosis) & Ketones | ADA (diabetes.org)

Westphal, S. A. (1996). The occurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis in non-insulin-dependent diabetes and newly diagnosed diabetic adults. Am J Med, 101(1), 19-24. DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00076-9

United States National Library of Medicine. Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Diabetic ketoacidosis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia

Merck Manuals. Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Quick Facts: Diabetic Ketoacidosis – Merck Manuals Consumer Version