How to Calculate Net Carbs: Fibers & Sweeteners

Calculating net carbs might seem daunting and confusing until you know-how. Among health and nutrition experts and the low-carb community, whether to count net or total carbs is a controversial topic. The net carb claims on packaged foods might not accurately reflect the number of carbs your body absorbs. It’s helpful to know how your body processes different types of carbs and what exactly net carbs are, especially if you have weight loss, health, or fitness goals. Here’s what you need to know about how to calculate net carbs on keto.

What are Net Carbs?

Net carbs might also be called impact or digestible carbs — simple and complex carbs that are absorbed by your body. Simple carbs are found in vegetables, fruits, syrup, honey, and other foods. Simple carbs have one or two sugar units connected together.

Complex carbs can be found in starchy vegetables like potatoes and in grains. Complex carbs have multiple sugar units linked together.

Your body can only absorb single units of sugar. When you eat a food containing carbohydrates, enzymes produced in your small intestine break down most of the carbs into individual sugar units. Some carbs are only partially broken down and absorbed, and others can’t be broken down into individual sugars, such as sugar alcohols and fiber.

Because of this fact, many nutrition and low-carb experts believe when you’re calculating net carbs, you can subtract most fiber and sugar alcohols from your total carb count.Your body processes sugar alcohol and fiber carbs differently than digestible carbs. For more on net carbs and fiber, check out Dr. Lowery’s informative article. For more on sugar alcohol, read our Sugar Alcohol 101 article.

Do You Subtract Fiber From Total Carbs?

Unlike sugar and starch, naturally occurring fiber is a unique form of carbohydrates that isn’t absorbed in your small intestine. The enzymes in your digestive tract can’t break down the links between the sugar units, so the fiber passes directly into your colon [1].

What happens after that depends on the type of fiber. Fiber is categorized into two types: Insoluble and soluble.

Put simply, insoluble fiber doesn’t dissolve in water and might help prevent constipation. Insoluble fiber leaves your colon unchanged, doesn’t provide any calories, and doesn’t affect your insulin levels or blood sugar [2].

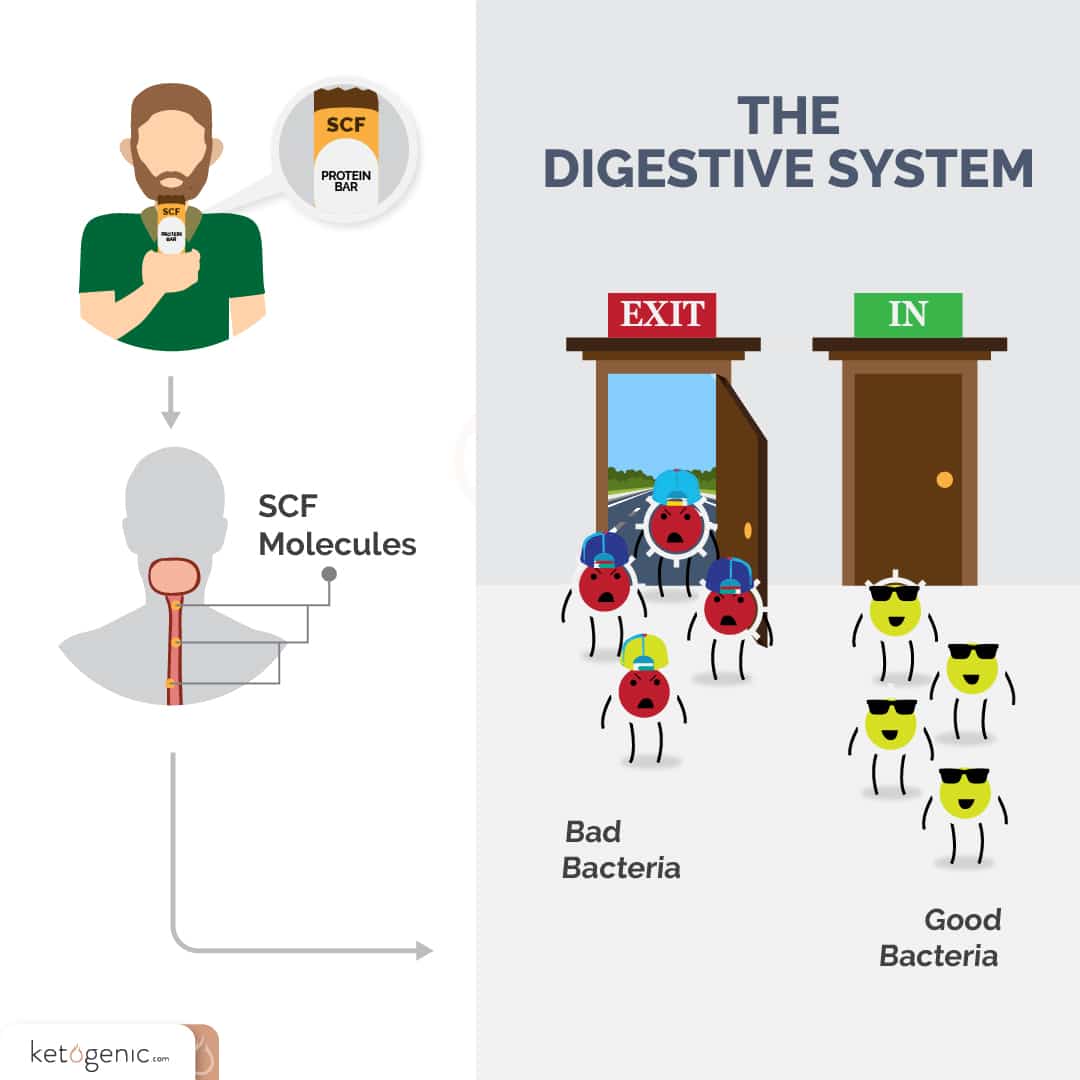

Soluble fiber dissolves in water and makes a gel, which can slow food’s movement through your digestive system and might help you feel more satiated [3]. Bacteria in your colon then ferments these soluble fibers into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that improve gut health and might also provide a range of other health benefits.

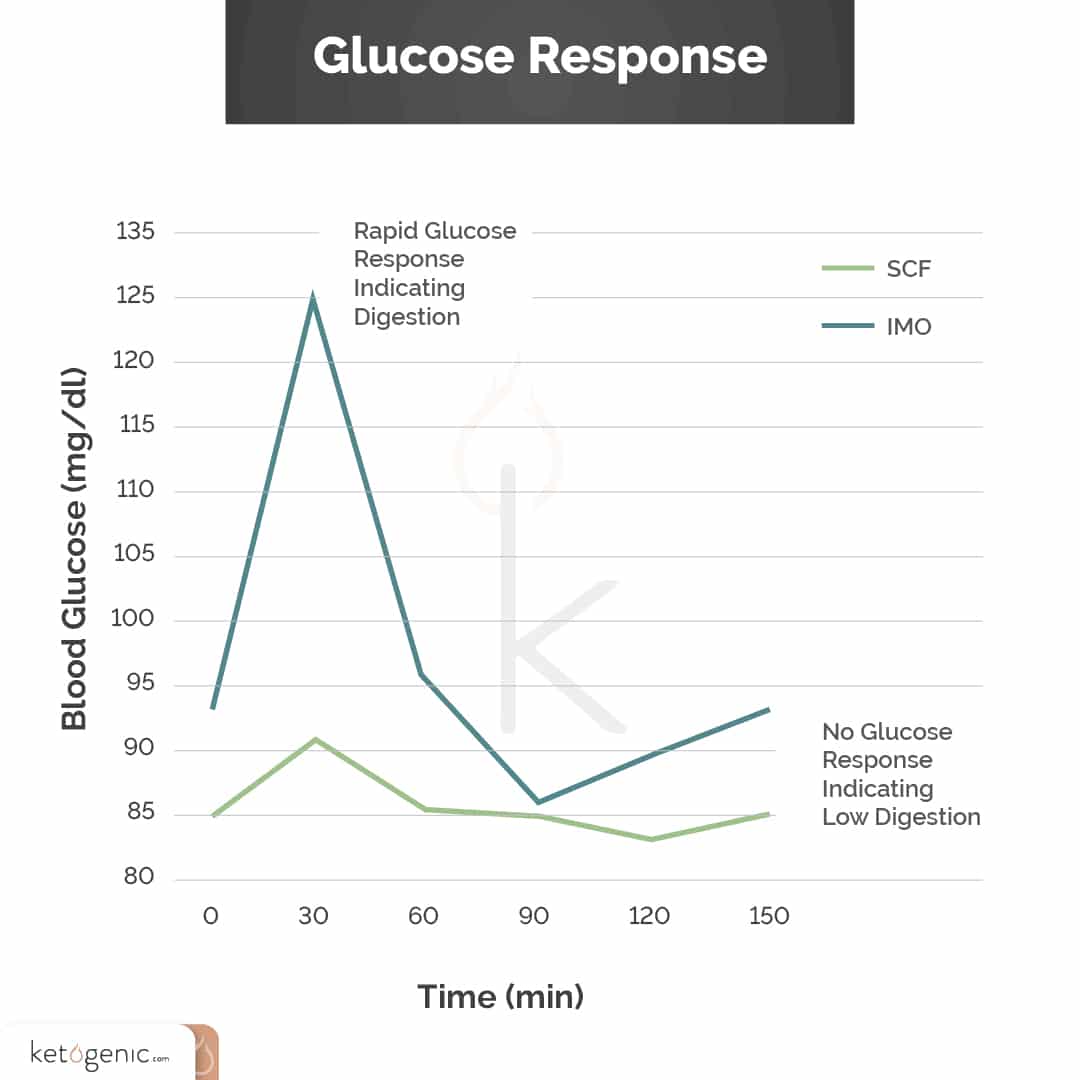

While soluble fiber does give you a few calories, it doesn’t seem to spike blood glucose. Most research suggests soluble fiber might even help reduce blood sugar levels [6] [7]. Studies also show soluble fiber might lead to the absorption of fewer calories, improved blood sugar control, and increased insulin sensitivity [8] [9] [10] [11].

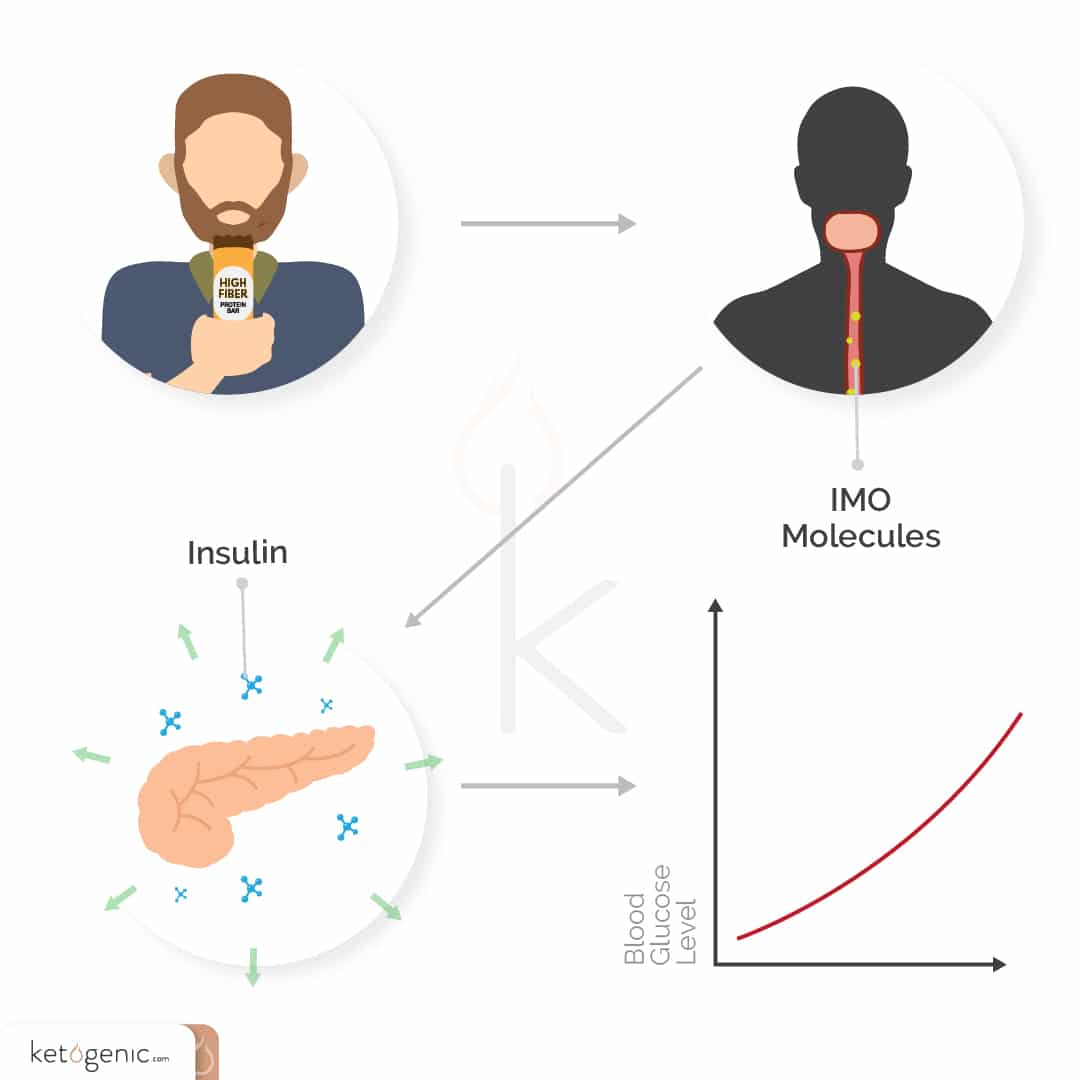

One possible exception to this rule is isomaltooligosaccharide (IMO) — a type of processed fiber. Like non-fiber carbs, IMO seems to be partially absorbed in the small intestine, and might raise blood sugar for some people. Many nutrition experts believe IMO isn’t a true fiber.

Are Sugar Alcohols Subtracted from Total Carbs?

Sugar alcohols are used to sweeten lots of low-carb, keto-friendly, and sugar-free food products. Sugar alcohols are processed in a similar fashion to fiber, with a few key differences. Your small intestine only partially absorbs many of the sugar alcohols. Studies show the small intestine absorbs 2-90% of sugar alcohols, but some are only briefly absorbed into the bloodstream before being excreted in urine.

Sugar alcohols can have different effects on insulin levels and blood sugar, but these effects are still significantly lower than sugar. For example, the glycemic and insulin index of glucose is 100. By comparison, the sugar alcohol erythritol has a glycemic index of 0 and an insulin index of 2. Another commonly used sugar alcohol, xylitol has a glycemic index of 13 and an insulin index of 11. Maltitol has an insulin index of 27 and a glycemic index of 35 [14].

Maltitol is often used in processed foods, like sugar-free candy and low-carb protein bars. It’s partially absorbed in the small intestine, and bacteria ferment the rest in the colon. Maltitol contributes around 3-3.5 calories per gram, compared to 4 calories per gram for sugar [15] [16] [17].

Maltitol has been reported to heighten blood sugar levels in those with diabetes and prediabetes. Some studies show other sugar alcohols are partially absorbed and might also raise blood sugar, but to a lesser extent than maltitol. The downside is for some people, these sugar alcohols also seem to cause bloating, gas, and other digestive troubles [18] [19].

When it comes to net carbs and sugar alcohols, the best choice seems to be erythritol. Around 90% of erythritol is absorbed in the small intestine and then excreted in urine. The other 10% is fermented to SCFAs in your colon, so it’s essentially free of calories and carbs and unlikely to cause or exacerbate digestive issues [20] [21].

More research on sugar alcohol is needed, particularly involving testing blood sugar levels. Overall, sugar alcohols like erythritol and xylitol don’t significantly affect insulin levels and blood sugar, but individual responses might vary, especially in those with diabetes and prediabetes. Sugar alcohols like maltitol and sorbitol should be avoided on a ketogenic diet.

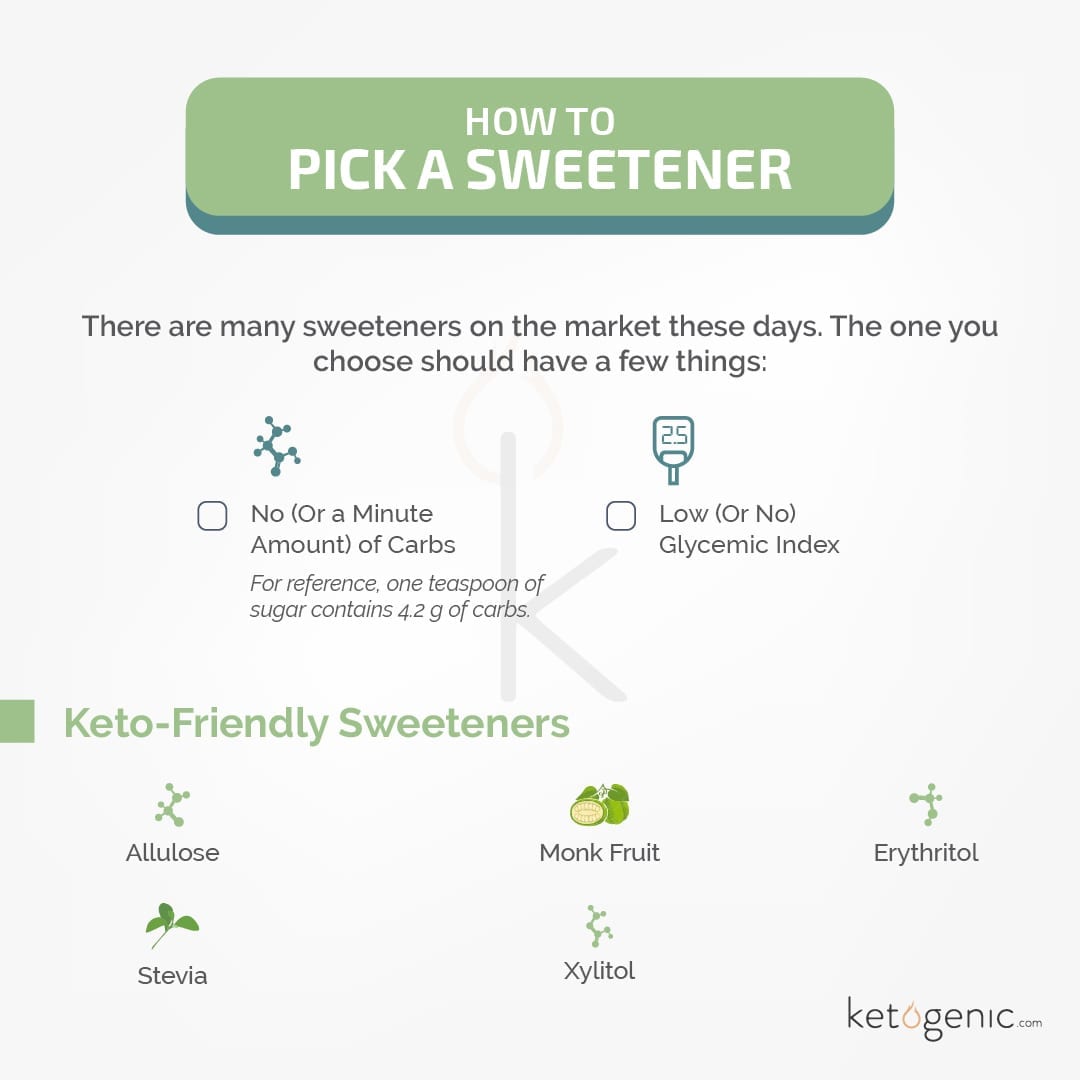

Other Sweeteners

Other ketogenic sweeteners can be completely subtracted from the total carbohydrate count because, similar to sugar alcohols, they are not digested and do not have an impact on glucose levels. These sweeteners include

How Do I Calculate Net Carbs?

After determining your daily macros, you might want to figure out your net carbs. The formula for calculating net carbs is:

Total carbs – fiber – certain sugar alcohols = net carbs.

Whole foods have natural fiber, so you can simply subtract the fiber from the total carbs to get the net carb count. You can find the nutrition info and carb and fiber content of thousands of foods in the handy USDA Food Composition Databases. For example, a medium avocado has around 17.1 grams of total carbs, and 13.5 grams of this is fiber. In this case, you calculate 17.1 grams of total carbs – 13.5 grams of fiber = 3.6 grams of net carbs [22].

Generally speaking, if you’re calculating net carbs in a packaged or processed food, you can subtract most fiber from the total carbs stated on the nutrition label. If you live outside the United States, the line that shows the total carbohydrates usually already has the fiber removed and listed separately.

If the fiber isomaltooligosaccharide (IMO) is on the ingredients list, it’s best to only subtract half of the fiber carbs.

Most sugar alcohols don’t count toward your net carbs on keto, but some do, so you shouldn’t discount them entirely. The following sugar alcohols are the best keto choices and don’t count toward net carbs for keto:

- Erythritol

- Xylitol

- Lactitol

- Mannitol [23]

However, some of the other sugar alcohols should be at least partially counted, such as:

- Glycerin

- Maltitol

- Sorbitol

- Isomalt

With these sugar alcohols, you take the total grams of the sugar alcohol, divide by 2, and add it to your carb count. Subtract half of the carbs from sugar alcohols from the total carbs listed on the ingredients label [24].

Remember, this value might look different than the number of net carbs on the product label since many companies subtract all sugar alcohol and fiber carbs when calculating net carbs listed on their products.

Conclusions About Calculating Net Carbs

To summarize:

- Net carbs are mostly starches and sugars. Net carbs are the carbohydrates your body processes and uses for energy

- Fiber and some sugar alcohols aren’t counted as net carbs for keto purposes

- Erythritol seems to be the best choice in terms of net carbs since many of the other sugar alcohols can raise insulin and blood sugar at least slightly

- To calculate net carbs in natural whole foods, subtract the fiber from the total carb count

- To calculate net carbs in processed foods, subtract the fiber and half the carbs from certain sugar alcohols

- Isomaltooligosaccharide (IMO) is an exception to the fiber rule that seems to be partially absorbed in the small intestine, and might raise blood sugar for some people

- If isomaltooligosaccharide (IMO) is on the ingredients list, it’s best to only subtract half of the fiber carbs

Calculating net carbs can help promote a higher fiber intake for those living the low-carb lifestyle. Fiber has been associated with increased satiety and decreased blood sugar. Calculating net carbs can be particularly helpful for those trying to lose weight and those with blood sugar concerns and certain medical conditions.

It isn’t 100% accurate, and it’s impossible to figure out net carbs with absolute precision due to the varying effects of processing on fiber, and other factors and variables. Some people find it easier to manage blood sugar by counting all carbs.

Ultimately, it’s up to you whether you count total or net carbs or whether you count carbs at all.

Do You Calculate Net Carbs on Keto?

Do you track total or net carbs? Comment below and share your experience with tracking carbs on keto!

References

Wheeler, M. L., & Pi-Sunyer, F. X. (2008). Carbohydrate issues: Type and amount. Journal of the American Dietetics Association, 108(4 Suppl 1), S34-39.

Lattimer, J. M., & Haub, M. D. (2010). Effects of dietary fiber and its components on metabolic health. Nutrients, 2(12), 1266-1289.

Howarth, N. C., Saltzman, E., & Roberts, S. B. (2001). Dietary fiber and weight regulation. Nutrition Reviews, 59(5), 129-139.

Oku, T., & Nakamura, S. (2014). Evaluation of the relative available energy of several dietary fiber preparations using breath hydrogen evolution in healthy humans. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology, 60(4), 246-254.

Roberfroid, M. B. (1999). Caloric value of inulin and oligofructose. Journal of Nutrition, 129(7), 1436S-1437S.

Mithieux, G., & Gautier-Stein, A. (2014). Intestinal glucose metabolism revisited. Diabetes Research in Clinical Practice, 105(3), 295-301.

De Vadder, F., Kovatcheva-Datchary, P., Goncalves, D., Vinera, J., Zitoun, C., Duchampt, A., Backhed, F., & Mithieux, G. (2014). Microbiota-generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut-brain neural circuits. Cell, 156(1-2). 84-96.

Brennan, M. A., Derbyshire, E., Tiwari, B. K., Brennan, C. S. (2012). Enrichment of extruded snack products with coproducts from chestnut mushroom (agrocybe aegerita) production: Interactions between dietary fiber, physicochemical characteristics, and glycemic load. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry, 60(17), 4396-4401.

Weickert, M. O., & Pfeiffer, A. F. H. (2008). Metabolic effects of dietary fiber consumption and prevention of diabetes. Journal of Nutrition, 138(3), 439-442.

Anderson, J. W., Baird, P., Davis, Jr, R. H., Ferreri, S., Knudston, M., Koraym, A., Waters, V., & Williams, C. L. (2009). Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutrition Reviews, 67(4), 188-205.

Baer, D. J., Rumpler, W. V., Miles, C. W., Fahey, Jr, G. C. (1997). Dietary fiber decreases the metabolizable energy content and nutrient digestibility of mixed diets fed to humans. Journal of Nutrition, 127(4), 579-586.

Oku, T., & Nakamura, S. (2003). Comparison of digestibility and breath hydrogen gas excretion of fructo-oligosaccharide, galactosyl-sucrose, and isomalto-oligosaccharide in healthy human subjects. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57(9), 1150-1156.

Kohmoto, T., Tsuji, K., Kaneko, T., Shiota, M., Fukui, F., Takaku, H., Nakagawa, Y., Ichikawa, T., & Kobayash, S. (1992). Metabolism of (13)C-Isomaltooligosaccharides in healthy men. Bioscience, Biotechnology, & Biochemistry, 56(6), 937-940.

Livesey, G. (2003). Health potential of polyols as sugar replacers, with emphasis on low glycaemic properties. Nutrition Research Reviews, 16(2), 163-191.

Langkilde, A. M., Andersson, H., Schweizer, T. F., & Wursch, P. (1994). Digestion and absorption of sorbitol, maltitol, and isomalt from the small bowel. A study in ileostomy subjects. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 48(11), 768-775.

Beaugerie, L., Flourie, B., Marteau, P., Pellier, P., Franchisseur, C., & Rambaud, J. C. (1990). Digestion and absorption in the human intestine of three sugar alcohols. Gastroenterology, 99(3), 717-723.

Beaugerie, L., Flourie, B., Pellier, P., Achour, L., Franchisseur, C., & Rambaud, J. C. (1991). Clinical tolerance, intestinal absorption, and energy value of four sugar alcohols taken on an empty stomach. Gastroenterologie, Clinique et Biologique, 15(12), 929-932.

Vaaler, S., Bjorneklett, A., Jelling, I., Skrede, G., Hanssen, K. F., Fausa, O., & Aagenaes, O. (1987). Sorbitol as a sweetener in the diet of insulin-dependent diabetes. Acta Medica Scandinavia, 221(2), 165-170.

Natah, S. S., Hussien, K. R., Tuominen, J. A., & Koivisto, V. A. (1997). Metabolic response to lactitol and xylitol in healthy men. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 65(4), 947-950.

Livesey, G. (2003). Health potential of polyols as sugar replacers, with emphasis on low glycaemic properties. Nutrition Research Reviews, 16(2), 163-191.

Ishikawa, M., Miyashita, M., Kawashima, Y., Nakamura, T., Saitou, N., & Modderman, J. (1996). Effects of oral administration of erythritol on patients with diabetes. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 24(2 Pt 2), S303-308.

Self Nutrition Data. Avocado, Raw, All Commercial Varieties.

Hiele, M., Ghoos, Y., Rutgeerts, P., & Vantrappen, G. (1993). Metabolism of erythritol in humans: Comparison with glucose and lactitol. British Journal of Nutrition, 69(1), 169-176.

Wolever, T. M. S., Piekarz, A., Hollands, M., & Younker, K. (2002). Sugar alcohols and diabetes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 26(4), 356-362.