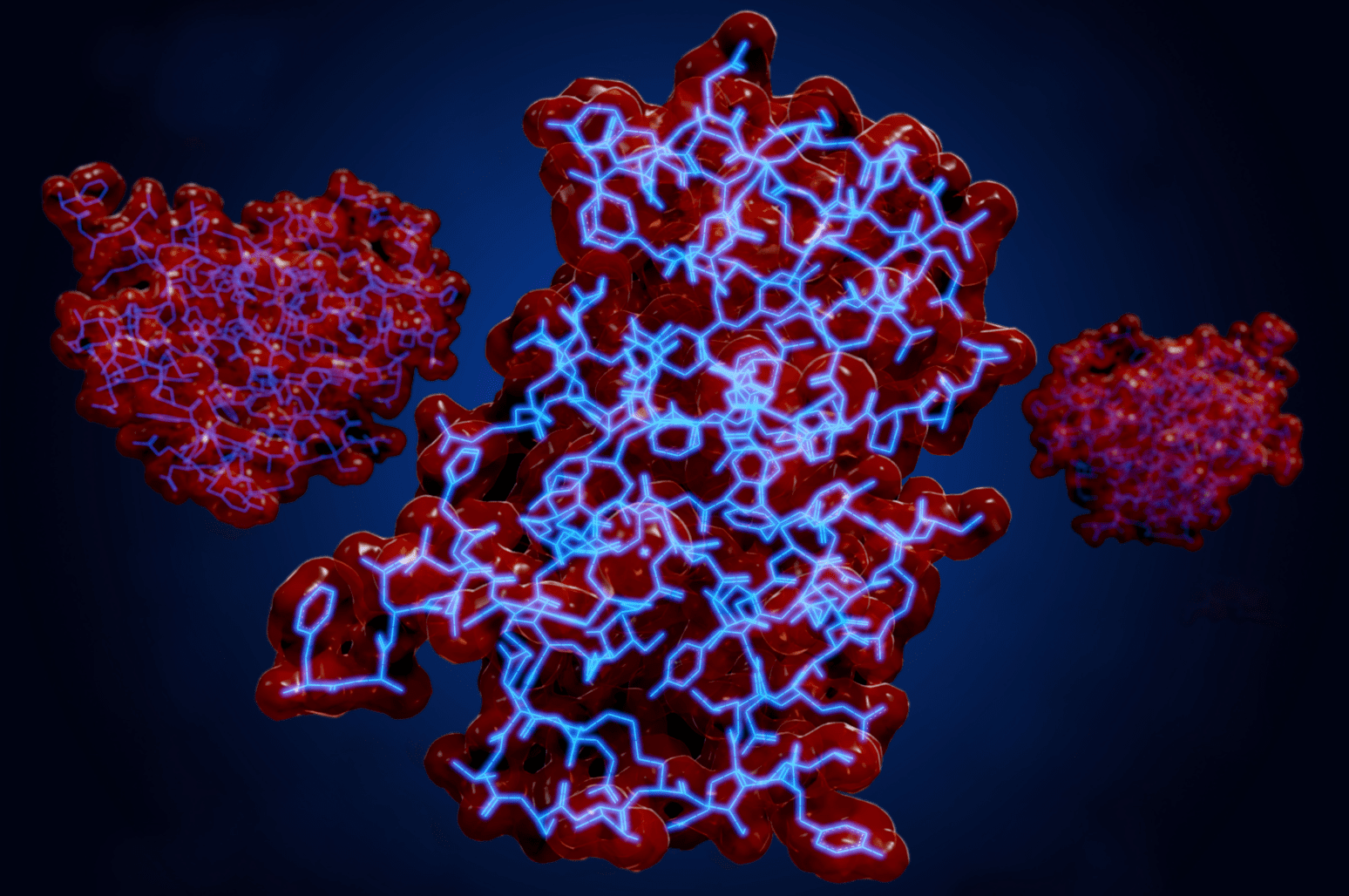

The word ketogenic may be synonymous with diet in today’s nutritional lexicon. However, a ketogenic state is simply that, a biological state. If you look up ‘ketogenic’ in a biochemistry textbook, it will typically tell you that ketosis occurs when carbohydrates are restricted to a certain threshold. This ultimately results in the formation of ketone bodies as a replacement energy substrate for glucose.

Is this known physiological process of keto just a fad diet that deserves to be labeled as such, or is it our modern way of eating that should be under scrutiny?

The Stigma Around Keto

Unfortunately, keto may not only be viewed as a fad, but also as a less preferred alternative–some go as far as to call it a dangerous physiological state, but this can’t be further from the truth. One of the problems with this approach to ketosis is that it creates a stigma surrounding low-carbohydrate nutrition which can have serious negative consequences.

Practitioners may be far less likely to try a strategy that may result in improved metabolic outcomes for their patients.

Dietary guideline committees are less likely to consider the emerging and robust body of evidence highlighting low-carbohydrate nutrition in the amelioration of many disease states.

Moreover, people may be less likely to embark on self-experimentation on their own for fear of what their doctor, friends, and family may think of such a ‘radical’ approach to nutrition.

Ironically, keto has been labeled as an extreme diet in some circles, however, others may argue that the extremist approach is the mainstream recommendation of several hundred grams of carbohydrates per day. Only in the past few decades has it been commonplace for daily consumption of high levels of carbohydrates, as well as 71 grams of added sugar. Our bodies are simply not meant to synthesize those amounts, thus leading to an epidemic of blood sugar-related diseases.

Is Keto Truly Radical?

Seen through a modern lens, it is easy to think carbohydrate restriction, fasting, or high-fat diets are radical or even dangerous endeavors. Food availability is at a place never seen before in history. Seemingly, there is no place where you do not have access to an abundance of cheap and processed foods–shopping malls, gas stations, donuts shops, convenience stores, and a Starbucks on every corner. Even clothing stores will usually have gumball or candy machines at the exit to tempt that last 25 cents out of your pocket, and cure that sugar fix.

The world we live in now would seem like a foreign land even to our recent relatives of the early 20th century. But what is common is not always normal and what may be normal is not always optimal. A brief history lesson may help provide you with the facts necessary to explain your dietary decisions when questioned by well-meaning friends and family.

Keto and Human Biology

Biologically speaking, our bodies are virtually the same as they were during the Paleolithic era. This represents a unique problem or evolutionary mismatch in the light of a modern-day food environment that does not resemble that time period.

The advent of agriculture and the more recent Industrial Revolution represent alterations in our collective lifestyles that cannot be offset by genetic adaptations in such a short time period.

Feast and famine were a routine part of life for our ancestors and we have biological adaptations that represent that cycle. For example we have but one hormone dedicated to lowering blood sugar levels yet we have multiple mechanisms designed to raise it including glucagon, epinephrine, and cortisol. This would suggest that we are adapted to deal with more frequent bouts of low blood sugar in the form of seasonal carbohydrate scarcity and starvation rather than an abundance of blood sugar-elevating foods on a chronic basis.

We may use intermittent fasting or ketogenic nutrition to mimic what were ancestral norms but to our biology, this is what is normal.

Intermittent Fasting and Calorie Restriction Study

A recent paper published in Molecular Psychiatry examined intermittent fasting versus caloric restriction in a mouse model, and how they may relate to neurogenesis (the creation of new neurons in the brain). The three-month study focused on brain genes (known as klotho) which are important regulators of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. [1] The mice were divided into three groups–one regular feeding schedule group, another intermittent fasting group, and the third consisted of caloric restriction.

At the end of the three months, the mice in the intermittent fasting group had improved long-term memory retention compared to the other groups. [2] Authors concluded that intermittent fasting could lead to long-term memory improvements in human adults.

It’s imperative to bypass some of the misleading keto fad headlines and soundbites, and dig into the biochemistry and evolution of human physiology to determine if keto, is in fact, a nutrition plan that is well-matched for the human body. The beauty of the scientific method is that we get to hypothesize, test, sometimes test again, and learn something we didn’t know before.

While the keto nutrition plan may not be the right fit for everyone, it boasts an array of scientifically proven benefits and can lead to positive health outcomes for many. Despite the fact that ketogenic diet and intermittent fasting may fall under some speculation, both are in alignment with human biology.

Food is information…feed with a purpose!

References

Dias, G.P., Murphy, T., Stangl, D. et al. Intermittent fasting enhances long-term memory consolidation, adult hippocampal neurogenesis, and expression of longevity gene Klotho. Mol Psychiatry. 2021; doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01102-4

Li, L., Wang, Z., & Zuo, Z. (2013). Chronic intermittent fasting improves cognitive functions and brain structures in mice. PloS one, 8(6), e66069. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066069